- Scientists are questioning the green credentials of hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles

- The Toyota Mirai is the official car of the 2024 Paris Olympics

- Hydrogen tech failed at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

A group of 120 scientists, engineers, and academics have drafted an open letter to the organizers of the Paris Olympics, rallying to ditch the Toyota Mirai as the event's official car and claiming the green credentials of hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles are questionable.

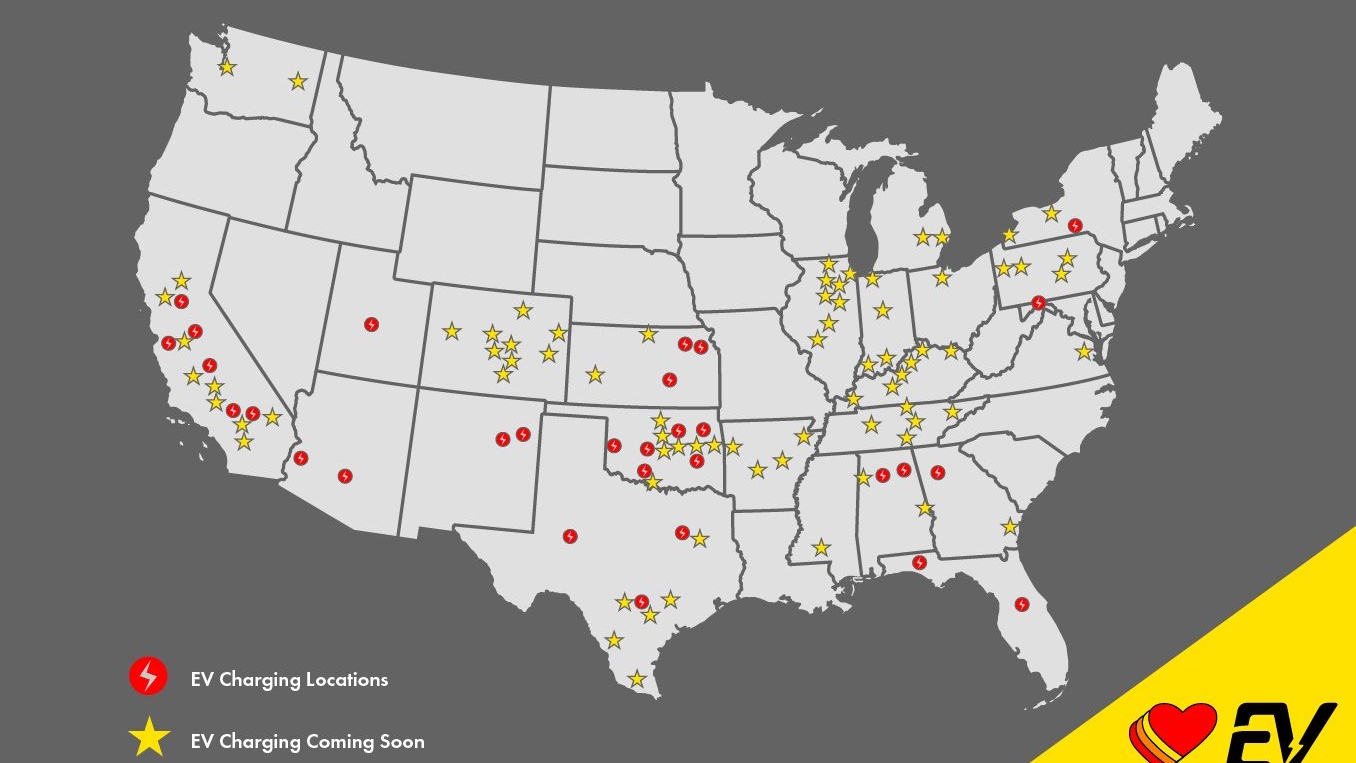

The letter urged Olympics organizers to replace the Mirai with a battery-electric vehicle as the official car because EVs "represent the most effective way to decarbonize passenger transport" and that promotion of fuel-cell vehicles "ultimately risks distracting and delaying from the real solutions we have available today."

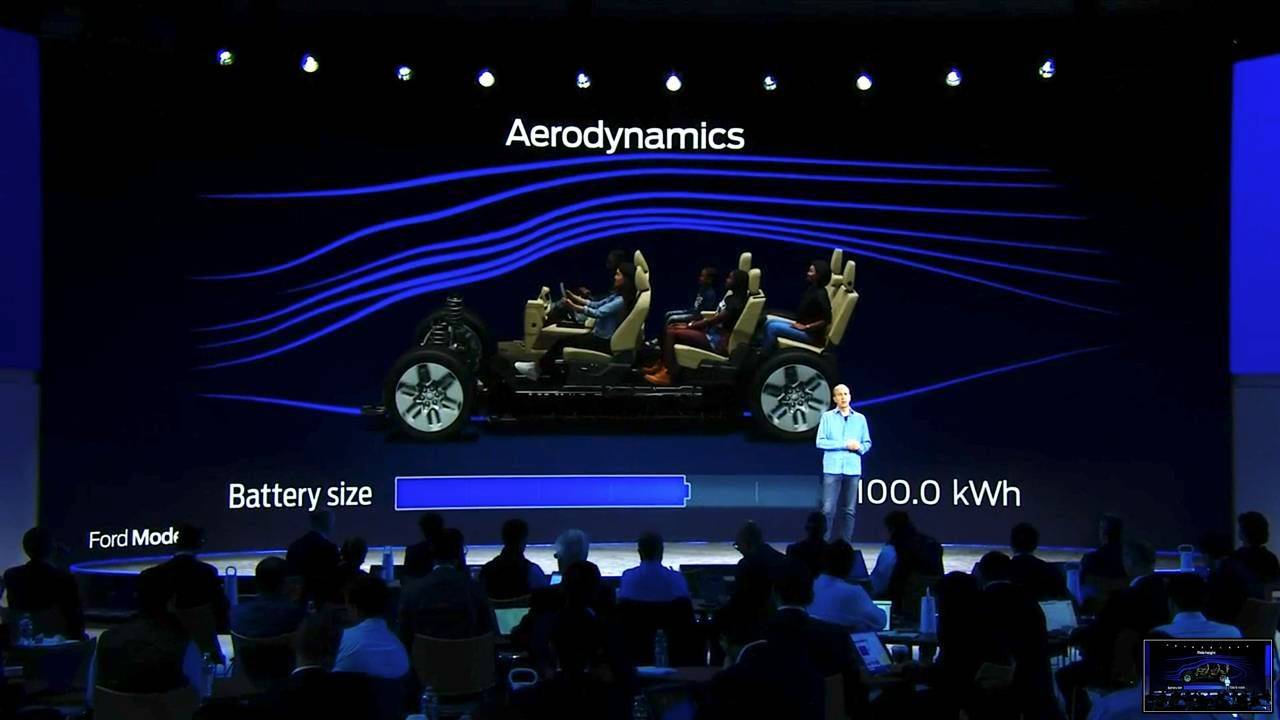

Unlike electricity, hydrogen is not an energy source, the letter notes, adding that 99% of hydrogen today is made from fossil fuels. It also noted that while it is possible to produce "green hydrogen" using renewable energy, fuel-cell vehicles require three times more of that energy than battery-electric vehicles.

2022 Toyota Mirai Limited

Ultimately, it's hard to see hydrogen as having a lower carbon footprint per mile versus battery electric—unless the hydrogen is used not as a vehicle fuel but as an energy buffer to help green the grid.

Hydrogen is also impractical due to high costs and low availability of both vehicles and fueling infrastructure, the letter noted. Hydrogen was also long ago due to be at cost parity with gasoline. But it has instead become more expensive in recent years.

Drivers of the current generation of fuel-cell vehicles, limited to California for the U.S., have had to deal with multiple waves of hydrogen supply issues that have rendered their vehicles undrivable at times. That's led to buybacks and other manufacturer subsidies like loaner cars.

Toyota Mirai and fuel-cell semi

Hydrogen tech already failed at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, the letter added. Despite promises by the Japanese government (and Toyota, which was also involved in those games) that fuel-cell cars and buses would be used extensively, and that the athletes' village would run on electricity made from hydrogen, a limited supply meant buses only ran on short routes, using "gray hydrogen" with overall emissions higher than diesel fuel, according to the letter.

Outside the Olympics, Toyota has recently suggested it's seeking to further develop combustion engines burning hydrogen—which would not be zero-emission vehicles. It's also looked to broaden fuel-cell semi plans for the U.S.—with a larger-battery approach that might translate to pickups or commercial trucks.