Hybrids and plug-in electric cars probably get more press than they deserve, given how small their numbers are in the vehicle fleet.

The U.S. has roughly 250 million vehicles on the roads, of which less than 2 percent are hybrids and plug-ins of all kinds.

Nonetheless, both technologies are important because they're at the leading edge of the electrification of the automobile.

Car as appliance

If you think about it, a car is one of the last major consumer appliances that doesn't run on electricity.

Not only are most home appliances electric--though not all, certainly--so are outdoor appliances like weed-whackers, lawn mowers, and the like.

We won't all be driving plug-in cars tomorrow. Or by 2020. Or even by 2050.

But the proportion of electrically-run accessories and powertrains in the fleet will increase significantly starting ... well, about now.

Electric power steering

If you buy a smaller car from pretty much any maker these days, you may (or may not) have noticed that its power steering is no longer hydraulic.

Instead, a majority of new cars are now fitted with electric power steering (EPS) that uses an electric motor to move the steering rack or arms, which saves weight and power.

Feedback then has to be simulated through some fairly sophisticated software that looks at what the front wheels are actually doing, and weights the steering wheel in the driver's hands accordingly.

Some makers are better at it than others--we like Mazda's EPS, we generally don't like Toyota's--but hydraulic power steering is conclusively on its way out.

Next, air conditioning

Hybrids and plug-in cars also now have electric air-conditioning compressors, so that the climate control remains on even when a hybrid's engine switches off.

2010 Toyota Prius 1.8-liter gasoline engine, with no accessory drive belts

Those compressors are still more expensive than the old compressors driven by a belt running off the engine's crankshaft pulley, and many of them require a high-voltage battery pack found only in hybrids or electrics.

But that's another accessory that will move toward electrification.

In fact, many makers are working toward the "beltless" engine--using the internal-combustion powerplant solely to provide motive power for the vehicle, with everything else that might sap power being run electrically.

Ford even built a prototype car that plugs in at night just to recharge a battery that powers the accessories--but doesn't power the car.

Tougher 2025 efficiency rules

Again, it's all in service of meeting the much tougher 2025 fuel-economy rules, while automakers do their absolute best to keep changes to user perceptions of how cars actually function to a minimum--or invisible.

So what are the technologies that will let automakers comply with the gas-mileage rules--and how will they change your next car?

- Part I: New Gas Mileage Rules Will Reshape What Americans Drive: Aerodynamics And Weight

- Part II: New Gas Mileage Rules Will Reshape What Americans Drive: Engines And Transmissions

- Part III: New Gas Mileage Rules Will Reshape What Americans Drive: Hybrids, Electrics, Cost

Polar Charging Post and Nissan Leaf

HYBRIDS and PLUG-IN ELECTRICS

An entire book could be written on the increase in what's called electrification in tomorrow's cars, but here's the bottom line.

We're keeping this fairly terse, due to the extensive coverage of plug-in electric cars and hybrid cars otherwise.

Hybrid cars, which have stayed at 2 to 3 percent of the market for a few years now, are likely to grow as a percentage of total vehicles sold.

The Toyota Prius--now a four-car lineup--is by far the best-known hybrid, not only in the U.S. but in the world.

Hybrid-electric technology, however, is now offered by Audi, BMW, Buick, Chevrolet, Ford, Honda, Hyundai, Kia, Mercedes-Benz, Porsche, and Volkswagen.

More makers will join the list in the years to come, especially among prestige brands (Jaguar and Land-Rover will join the list soon, for instance).

Fast, heavy luxury cars can better absorb the additional costs of hybrid technology, and their much better noise suppression make the differences in the drivetrain operation less apparent than in stripped-down economy cars.

Mild vs full hybrids

There are fundamentally two types of hybrid-electric vehicles: Those with "mild hybrid" systems, which recapture energy under regenerative braking but can only use that to supplement engine torque, and to restart the engine after a stop.

In other words, their electric motors are too small to move the car on their own, even if they assist the gasoline engine and let it run much more efficiently.

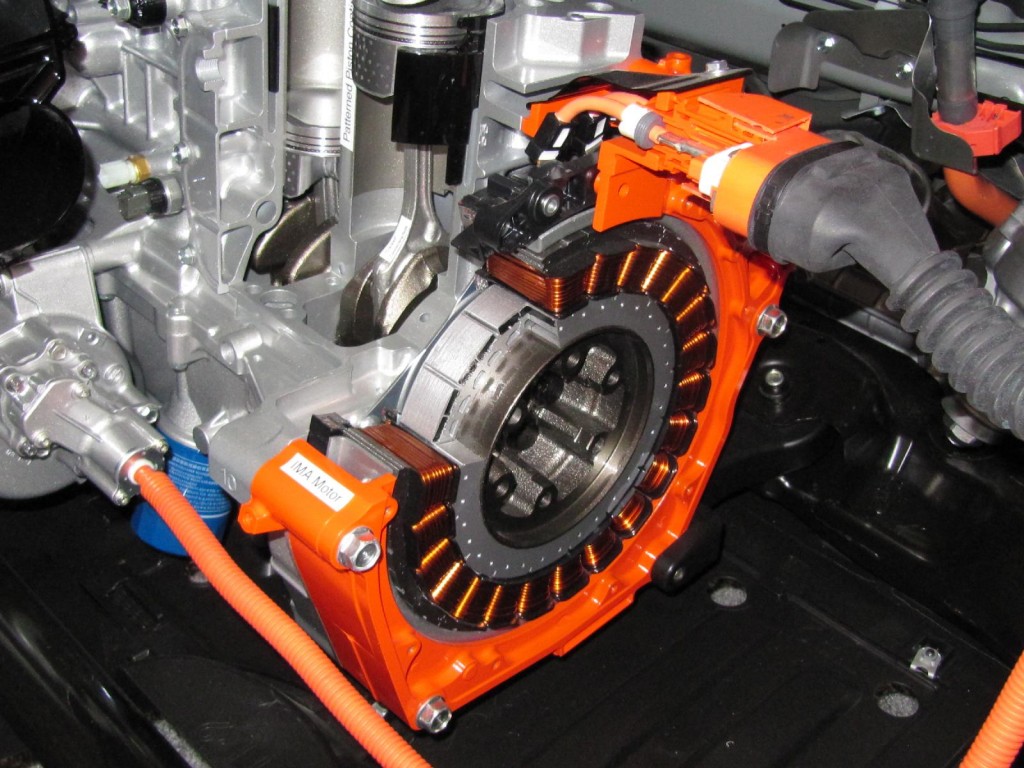

2012 Honda Civic Hybrid - Integrated Motor Assist electric motor cutaway

Honda is the best-known proponent of this approach, with multiple generations of its Integrated Motor Assist (IMA) system using 10- or 15-kilowatt (15- or 22-hp) motors attached to four-cylinder engines.

General Motors uses a similar system, known as eAssist in various Buick models and used in certain "Eco" models for Chevrolet.

That system replaces the conventional alternator with a belt-driven electric motor-generator that can act as a starter, an alternator, or a traction motor.

It can start the engine, charge the battery under regenerative braking, or deliver electric power to the engine to avoid downshifts that boost fuel consumption.

One- or two-motor full hybrids

Then there are the full hybrid systems, from Toyota, Ford, and more recently Hyundai and Kia, Honda, and many others.

Those provide at least some ability to power the car solely on electricity stored in the hybrid battery pack.

Some of these systems use a single motor-generator, sandwiched between the engine and an automatic transmission modified to function even with the engine off.

2013 Hyundai Sonata Hybrid drive event, NYC area, April 2013

That's the approach taken by Hyundai and Kia, the VW Group (Audi, Porsche, Volkswagen), and both BMW and Mercedes-Benz, among others.

Toyota, Ford, and Honda all use a pair of electric motors, allowing one motor to provide electric torque to the wheels while the other recharges the battery on engine overrun.

Two-motor systems require complex programming to maximize efficiency in all the energy flows among the engine, motors, and battery.

And one- and two-motor hybrid systems will likely coexist in the market for many years.

Plugs added to hybrids

Plug-in hybrids--now offered by Ford, Honda, and Toyota--will grow in number.

They're not for everyone--if your driving routines resemble those of a traveling salesman, you're better off with a diesel vehicle--but they're well-suited to urban and suburban traffic.

And many makers are now tuning their hybrids to deliver electric assistance or even all-electric running at highway speeds, unlike the first Toyota and Honda hybrids.

2013 Ford C-Max Energi plug-in hybrid, Marin County, CA, Nov 2012

Electric cars, with or without engines

Plug-in electric cars, now on the market for more than two years, will slowly gain adherents.

They're already selling better than the first hybrid-electric vehicles did at the same point in their life, but they're far more costly than gasoline cars of the same size and capacity.

Plug-ins will remain exotic for several more years, and their numbers will be low--both battery-electric cars like the Nissan Leaf and Tesla Model S, and electric cars with range extending gasoline engines, like the Chevrolet Volt and Fisker Karma.

Still, their buyers uniformly love them, and rave about the smooth, silent, torque-y nature of their cars.

And as battery costs come down steadily and the cost of gasoline cars rises (see below), slowly more buyers will be willing to consider them.

Costs will come down

Battery-electric cars with ranges of 70 to 100 miles won't likely be used as a household's only car, but with the average U.S. household now owning more than 2 cars, they make fine second cars.

Their hidden advantage? They're so efficient, and electricity is relatively so cheap against gasoline, that they generally cost one-third to one-fifth as much per mile to run as gasoline cars.

money

And maintenance on electric cars is pretty much limited to wiper blades and tires.

Even the brake pads last much longer, because they use regenerative braking to slow the car by turning the motor into a generator to put energy back into the battery pack as the car slows.

But plug-in cars will take a decade or more to reach significant market share.

In the near term, it's likely to be gasoline or diesel engines for you (or maybe a hybrid).

At least, until you discover that electric cars are much nicer to drive.

Then you'll have to decide how much--if anything--that's worth to you.

HIGHER COSTS

The amount of fuel saved by newer and more efficient vehicles is substantial, and over the average lifetime of a vehicle, it'll make a big difference in owners' gas bills.

Over five years, boosting the fuel economy of a car driven 15,000 miles a year from 20 mpg to 30 mpg saves 1,250 gallons of gas--or $6,000 assuming $4-per-gallon gasoline.

The problem is that the savings trickle in over time, whereas purchase price comes up front.

$3,000 more by 2025?

The EPA estimates that to comply with the 2025 CAFE rules, the price of an average vehicle will rise almost $3,000 in real dollars between 2012 and 2025.

That's a bit less than 10 percent of the average sale price of $31,000, but it's enough to price some marginal buyers out of the market for new cars.

And many automakers say privately they think the EPA's estimates are far too low, with some suggesting the real price increase could be double that.

Car companies, unfortunately, have a history of crying wolf over every new regulation--they fought seat belts, emission controls, airbags, crash-safety tests, gas-mileage rules, and essentially every other regulation that would affect their product--so it's hard to know what the real numbers are.

![2011 Chevrolet Volt and 2013 Tesla Model S [photo: David Noland] 2011 Chevrolet Volt and 2013 Tesla Model S [photo: David Noland]](https://images.hgmsites.net/med/2011-chevrolet-volt-and-2013-tesla-model-s-photo-david-noland_100427531_m.jpg)

2011 Chevrolet Volt and 2013 Tesla Model S [photo: David Noland]

Opening for electric cars

That may provide an opening for plug-in electric cars, as battery costs fall about 7 percent a year while the costs of combustion-engine cars are rising.

At some point--perhaps 2020, some suggest--mass-market buyers will start to consider plug-in cars when their price premium is no more than the difference between a gasoline car's lowest and highest trim level.

From now through 2025, however, it seems clear that the technology to make new cars more efficient will come at some price.

Unfortunately, lazy, wasteful, inefficient cars are simpler and cheaper to make today than ultra-efficient ones.

PREVIOUSLY ..

- Part I: New Gas Mileage Rules Will Reshape What Americans Drive: Aerodynamics And Weight

- Part II: New Gas Mileage Rules Will Reshape What Americans Drive: Engines And Transmissions

_______________________________________________